A defining moment for global health is about to unfold in Geneva.

The United Nations is playing a central role in efforts to prevent future pandemics, as the World Health Assembly works to finalise the text of the Pandemic Preparedness Treaty — a document born from the catastrophic failures and fragile victories of COVID-19.

The text of the treaty promises shared information, equitable access to vaccines and therapeutics, and stronger healthcare systems – all of which resonates deeply with the people who lived through the worst.

In 2020, at the height of the global pandemic, UN News spoke with many of the unsung heroes who faced impossible challenges with courage and resolve, including doctors, community workers, a journalist, a youth volunteer and an Indigenous leader.

They were exhausted, scared, hopeful and determined. Today, five years later, they carry scars and wisdom from that fight.

We went back to them – and their reflections remind us of what is at stake.

Margarita Castrillón, Paediatrician, Buenos Aires, Argentina

As a paediatrician on the frontlines, Dr Castrillon says future pandemic plans must start with empathy, solidarity, and real support for health workers.

“We were heroes without capes and without fair pay.”

In 2020, Dr Margarita Castrillón, a Colombian paediatrician living in Buenos Aires, found herself taking on far more than her usual clinic work.

As COVID-19 swept Argentina, she volunteered to also serve in emergency medical transport, riding in ambulances to transfer patients, many suspected of having the virus, to hospitals across the city.

After one of those long, exhausting shifts, she noticed a handwritten sign taped to the elevator in her apartment building.

It said “I’m Victoria from the 7th floor. If you need any groceries or help, ring my doorbell,” she recalls. “That gesture filled my soul after such a hard day at work. It marked me. I thought: ‘the good people outnumber the bad’. Empathy was winning.”

Dr Castrillón was working across multiple roles – clinic, ambulance, teaching at the university – all while raising her young daughter. “It was brutal. I look back and I want to cry. I’m not sure I’d be as brave if it happened again. Every day I left home terrified.”

The memory of Buenos Aires’ summer heat under full protective suits stays with her. “We were heroes without capes and without fair pay. We worked 24 hours, covering for sick colleagues, unable to eat or speak together.”

But the experience gave her one unexpected gift. “I taught my daughter to read, write and do maths at home. It made me a better mum. I valued family and true friendship more than ever.”

Her medical routine also changed permanently. “I now wear a mask with every patient. It protects both of us. And hand sanitiser stations in hospitals are permanent now.”

On the upcoming global pact, she is firm: “We need collaboration and love for people at the government level. We lived through hell. Some colleagues still suffer panic attacks. Recognition and fair pay are essential to keep health systems strong.”

Evgeny Pinelis, Intensive Care doctor, Brooklyn, New York

In an overwhelmed New York ICU, Dr Pinelis worked beyond limits and now warns the world may still be unprepared for what comes next.

When we first spoke to Dr Evgeny Pinelis in the spring of 2020, he was deep in New York City’s overwhelming first COVID wave.

“Our first severe patient came on 7 March. By the end of the month, we had over forty ICU beds full,” he recalled. ICU nurses were pushed beyond safe limits, caring for up to five critical patients at a time.

“I do hope there won’t be a next time, because I’m not confident we’re truly ready.”

Protective equipment ran so scarce that he bought supplies with his own money, while volunteers scrambled to donate gear, some uncertified, but “better than nothing.”

Throughout the crisis, Dr Pinelis shared dispatches on social media, chronicling the chaos with honesty and caution. “I woke up one morning to thousands of new followers,” he said.

Five years later, his reflection is sobering. “I can only speak about this from the perspective of a regular intensive care doctor. And if I had to sum it up, I’d say I realised I’m ready, if necessary, to work far beyond the norm and do everything possible when faced with a poorly understood disease that we didn’t quite know how to treat.”

The public’s reaction, he says, was a mixed bag. “On the one hand, there were volunteers, support, and solidarity. But on the other, there were conspiracy theories, complaints about things as trivial as closed theatres, and at times even hostility toward medical professionals and scientists.”

In the earliest days of the pandemic, positivity seemed to win out. “But within a month or so, the negativity began to dominate,” he says. “We were lucky that the disease turned out not to be highly lethal.”

As for preparedness today, Dr Pinelis remains cautious: “Being less prepared than we were in New York is hard to imagine – so yes, we can and should be better prepared. But it seems the lessons learned weren’t quite the ones we hoped for. And I do hope there won’t be a next time, because I’m not confident we’re truly ready.”

Chen Jingyu, lung transplant surgeon, Wuxi, China

Dr Chen performed emergency lung transplants on critically ill COVID patients and now advocates for global cooperation and fair access to care.

In 2020, Dr Chen Jingyu, vice president of Wuxi People’s Hospital and one of China’s leading lung transplant surgeons, performed the world’s first lung transplants on critically ill COVID-19 patients.

His team worked under extraordinary conditions, moving their operating theatre into an infectious disease hospital and taking extreme precautions to avoid infection.

“We didn’t know if there was any virus in their airways during the process of cutting off the diseased lung. So, we did the surgery with very strict precautions,” Dr Chen said at the time. “We had a very scientific discussion about how we could save lives, protect our healthcare workers, and achieve zero infection.”

“The Pandemic Treaty is a turning point in global health.”

Today, Dr Chen says the Pandemic Treaty represents a critical milestone. “The Pandemic Treaty is a turning point in global health governance. First, in terms of prevention and early response, the treaty will help build a global coordinated prevention system, strengthen pathogen monitoring and information sharing, and implement the One Global Village, One Health approach.”

“Second, the treaty provides legal guarantees for equitable access to medical resources, avoids national monopolies, and improves global standardisation of care capabilities to patients in severe conditions.”

Dr Chen believes the lessons of the pandemic must be used to build a fairer system. “Access to and training of high-end medical technologies will enhance the ability of developing countries to respond to severe diseases such as respiratory failure and reduce mortality,” he says.

“Only through international cooperation and scientific consensus can we truly have the courage and confidence to fight against pandemics.”

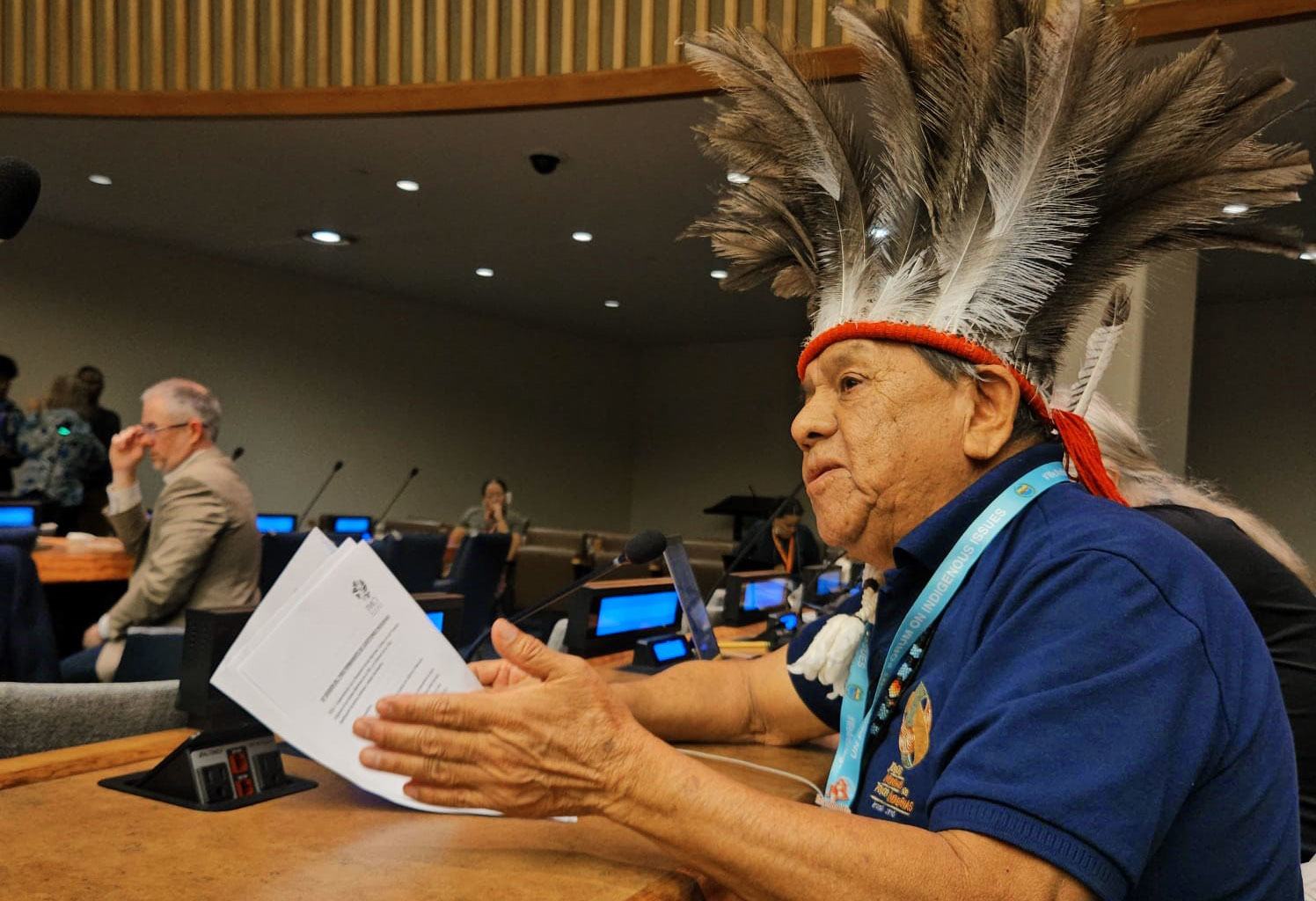

Marcos Terena, Indigenous leader, Brazil

Marcos Terena lost family to COVID and calls for a global pact rooted in dignity, life, and respect for the Earth.

The pandemic devastated Brazil’s Indigenous communities, including Terena’s own Xané people. “I still can remember that morning, in our Indigenous community, when we heard that a cousin of ours had passed away suddenly."

“He started coughing and ended up dying. That scared all of us in our community”.

“About two hours after his death, we learned that his wife, who had gone to the hospital to retrieve his body, had also died, from the same symptoms. We started panicking and looking for help, as this was a disease that even our leaders did not know how to handle, how to cure. They did not know much about this disease which was brought to us by the wind.”

The loss became personal when his brother, the creator of the Indigenous Olympic Games, also died of COVID-19. “It brought us emotion, tears. He went to the hospital and never came back.”

“The UN must make a pact for life”

Looking back, Mr Terena believes the World Health Organization played a crucial role. “When the WHO became the focal point and the mediator for the pandemic response, this gave the United Nations a very responsible role to play among governments across the globe,” he says.

Today, his message remains urgent and clear. “We are not talking about money or currencies. We are talking about well-being. We the Indigenous people fight for the Earth. The Earth is our Mother, and our source of life; it gives us our cosmovision, our food security and our dignity as peoples.”

As world leaders meet again, he leaves them with a final plea: “The UN should make a pact for life, a pact for dignity and a pact where life is crucial to all.”

Nikhil Gupta, United Nations youth volunteer, Varanasi, India

UNV's Nikhil Gupta created grassroots health and education tools during lockdowns, turning remote villages into hubs of volunteer-powered resilience.

As COVID-19 overwhelmed Varanasi, India’s spiritual heart, Nikhil Gupta – a United Nations Volunteer from Uttar Pradesh – stepped in to serve the most isolated communities.

“The pandemic changed everything,” he says. “In Varanasi, COVID-19 infected over 80,000 people, and thousands of families in remote villages were left without access to healthcare, education, or even accurate information. But the crisis revealed not just gaps but grit.”

Mr Gupta and his team launched creative grassroots solutions. “Guided by the UN principle of ‘Leave no one behind,’ we created an animated volunteer guide named Ganga – a friendly character with a warm voice and simple wisdom. Ganga became a beacon of hope, educating villagers about hygiene, safety, and vaccination through videos watched on shared mobile screens under neem trees.”

“When the world paused, we stepped forward. When fear spread, we spread hope.”

They also opened Vidya ki Jhopdi – The Hut of Education. “It was a community classroom built from scrap but powered by purpose. There I met Raju, an 11-year-old from a nearby slum who had lost access to school. He would sit on a worn-out mat every afternoon, eyes wide with wonder, scribbling letters in chalk. Today, he reads and writes fluently, and dreams of becoming a teacher.”

The human moments left the deepest impression. “There was Amma Shanti Devi, a 90-year-old widow in a remote village. Left alone after the lockdown, she hadn’t stepped out in months. Through our volunteers, she received regular wellness check-ins, medicine deliveries, and simply someone to talk to.”

Looking ahead to the Pandemic Treaty, Mr Gupta says that it shouldn’t be only technical or top-down. “It should echo the voices of people like Amma and Raju. It must include local wisdom, volunteer networks, and ensure grassroots equity. My message to world leaders? ‘Laws can guide, but love must lead. Invest in hearts that serve, not just in speed.’”

He adds: “Support young changemakers. Recognise the power of community-driven action. Make health systems inclusive. And build a world where, when the next storm hits, the light doesn’t dim. Because in every village, there’s a Nikhil. And in every Nikhil, a youth waiting to be led.”

Alejandra Crail, Journalist, Mexico City

Alejandra Crail exposed rising child abuse during lockdown and says future pandemic plans must protect mental and emotional health, too.

“Health is more than vaccines. It’s also mental health, emotional health.”

When the pandemic hit Mexico, Alejandra Crail was not just reporting the crisis, she was sounding an alarm. Her investigation, To Kill a Son, revealed that every two days in Mexico, a child under 15 is killed – often at home, and often by someone in their own family.

“Let me remember something,” she says. “At the beginning of the Coronavirus, I started to talk to different experts on childhood rights and domestic violence…We were worried because we were about to lose our eyes in schools, sports, and community centres. Children were more vulnerable than ever during the COVID era.”

For many, home wasn’t a safe haven. “Their houses were the most dangerous places for them, and their nearest family members are usually their attackers.”

Now, five years later, the violence hasn’t eased. “The number of domestic violence cases has increased after the pandemic,” Ms Crail says.

She shares one case she can’t forget. Joselina Zavala, a grandmother who reported the sexual abuse of her disabled grandson. “She went to the police…despite the testimony of the child and the proof, his father was absolved.

“When people go to the authorities to achieve some kind of justice… the authorities usually don’t investigate enough, and the crimes are unsolved.”

The pandemic also reshaped her personal convictions. “Health is the most important thing to make sure that we have,” she says. “When we live in a country like Mexico, where we don’t have a good public health system, a pandemic or any other illness can be very, very hard to survive.”

She adds, “Work isn’t the most important thing in the world. Family - your loved ones – are the real treasure. We need to spend more time with them, because we don’t know how much time we can share.”

Looking ahead to the World Health Assembly and the Pandemic Treaty, she warns that global responses must go beyond access to vaccines and medicine. “Health is more than vaccines. It’s also mental health, emotional health,” she says.

Her final message to world leaders is as personal as it is political: “We need to open paths that benefit all countries that make up the world. These issues must be on the table because in a pandemic, they can be the difference between a family surviving adversity, or not.”